A Scientist's Guide To Self-Improvement Science (For Non-Scientists)

There's a lot of info out there, and it's hard to tell what's good and what's not. So I asked a scientist friend for help. (Part 1 of 2)

Gidday Cynics,

Thanks for waiting for this newsletter. There’s a lot of info here, so I wanted to take extra time to make sure it was as solid as possible.

This one has been brewing for a while. A few weeks ago, I wrote about the need a lot of us feel to improve our sleep, and referenced a book called Why We Sleep, by neuroscientist and sleep specialist Dr Matthew Walker. My plan was to write another newsletter picking out what I thought was the good stuff from the book, while raising a few things I wasn’t so sure about. But, as several readers pointed out, the book was quite controversial. So I looked around online to see some of the reactions. Some suggested the book was merely unhelpful, creating sleep problems by increasing readers’ worry about their sleep. Others went as far as to say it was overtly harmful, or that it had been mostly or entirely debunked, which is itself a very big claim.

A couple of readers suggested I check out a podcast called Maintenance Phase, hosted by Michael Hobbes and Aubrey Gordon. I was happy to, because I was already a fan of one of the hosts, having subscribed to Michael’s Substack newsletter Confirm My Choices. Plus, the podcast topic — a skeptical look at wellness and health trends — seemed right up my alley.

Unfortunately, I hated it.

Your mileage may vary. For me it was like having my ears crucified. One host spends a great deal of time denigrating Walker’s personal appearance, which is something I absolutely can’t stand. Can we just leave people’s looks alone? This was followed by discussion about about how Walker “talks slowly,” and that the hosts had to listen to him on 2x speed, which is both unfair and ridiculous,1 because the way these hosts talk did not spark joy. They hail from the extremely American podcasting style of screaming with laughter every ten seconds at things that aren’t jokes, like an unlikable crew of randos that dominate the kitchen at a house party held by a friend of a friend. I suppose this can be fun, for people who are familiar with the hosts, but for a newcomer it’s agony. Here’s a brief sample of the dialogue, from memory:

We have to like, so I'm going to send you, so I'm sorry like

HAHAHAHAHAHAHA

Oh like, I know but I'm going to…

Hahahaha!

…send you a TED talk

HAHAHAAAAAA

HA HA HA HA HA

pfthllllbttttt

SNORT

HAW HAW HAW HAW HAW

Oh my godddddddd

I still haven’t finished the podcast, and I don’t know if I will. I told myself I’d listen to the rest of it while I mowed the lawns, only to find myself myself preferring the soothing cough of the lawnmower choking on over-long grass.2

To be fair, I don’t think there is necessarily anything wrong with ridiculing ideas that evidence shows are erroneous, misleading, or dangerous. If I did, I’d be a massive hypocrite. But I do think it important that the message not be completely lost in the medium, and I was dismayed to find myself so annoyed by the hosts that I felt inclined to disagree with everything they said. What’s more, the more I listened the more I felt that the hosts were guilty of exactly what they accused Walker of: indulging in hyperbole at the expense of evidence. And who can you trust, if you find yourself unable to trust the people doing the debunking?

I was desperate for answers. So I phoned — or rather, emailed — a friend.

Fortunately for me (and you), this friend is the smartest person I (or you) have ever met. Dr Lee Reid is a neuroscientist, and before he did that, he learned software development from books while writing code for a music composition program with voice-recognition software and a foot-operated mouse. The story of his recovery from a crippling, mysterious pain disorder is absolutely extraordinary and I encourage you to check it out. Choose from the prose version or comic-book version, illustrated by, uh, me. I’m stoked to have him here.

(Content warning: readers are advised that the following conversation contains references to self-harm and suicide.)

Hi, Dr Lee Reid, if that is your real name. Can you tell me a bit about yourself?

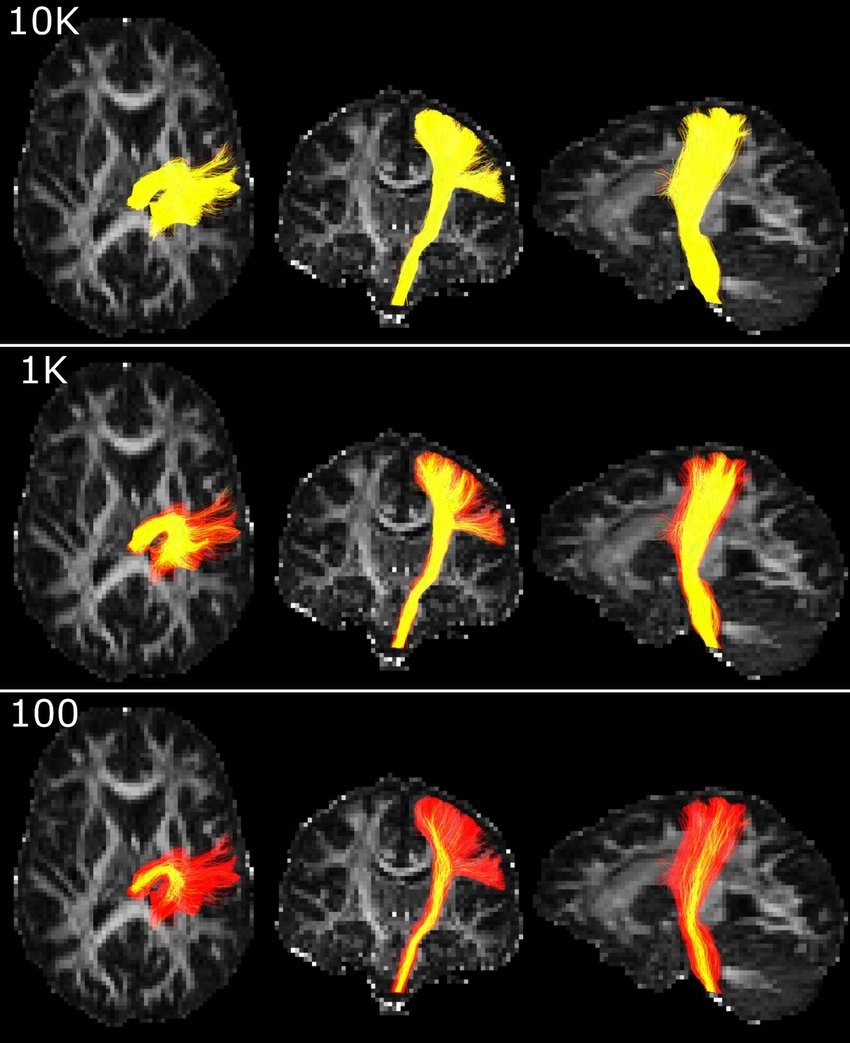

Sure. So, in short I'm a software engineer and neuroscientist. I began in Auckland, NZ, where I studied human physiology and medical science. I did my PhD at Australia's CSIRO and the University of Queensland, focusing on how we can use medical imaging, like MRI, to measure brain changes that represent learning or physical rehabilitation. That's an area where it can be easy to unintentionally make claims that ultimately don't stack up. Post PhD I developed imaging software to help clinicians plan safer brain surgery — work that I hope to continue at the University of California this year. Again, that's an area where detail is everything, and being picky in your science is fundamental to safety.

On the flip side, I've also spent some time in and around biomedical start-ups and in pure software engineering. In both these environments, workers are often pushed to "move fast and break stuff" while the business makes fairly wild claims in the interests of securing funding one way or another. I've also spent some time assessing articles made by Big Pharma about the cost vs benefits of their medicines — an area where there can be clear incentive to exaggerate but where making clearly inflated claims could backfire.

Cool, that's really helpful to know. So, this self-improvement experiment I'm doing — one of the things I ran into straight away was the sheer volume of either inflated claims or anecdotal stories or a lack of hard evidence or just full-on lies that riddle the field. As a journalist, I was keen to avoid the worst of this minefield by trying to stick with stuff that was well-evidenced, drew on expert research, or was written by experts, but I've run into problems there too. For instance, I've read a 2017 book called Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker, a neuroscientist at UC Berkeley. A few claims in the book raised my eyebrows, such as the claim that "sleep is a panacea;" and this passage (from the first page of the book):

Routinely sleeping less than six or seven hours a night demolishes your immune system, more than doubling your risk of cancer. Insufficient sleep is a key lifestyle factor determining whether or not you will develop Alzheimer’s disease. Inadequate sleep—even moderate reductions for just one week—disrupts blood sugar levels so profoundly that you would be classified as pre-diabetic. Short sleeping increases the likelihood of your coronary arteries becoming blocked and brittle, setting you on a path toward cardiovascular disease, stroke, and congestive heart failure. Fitting Charlotte Brontë’s prophetic wisdom that “a ruffled mind makes a restless pillow,” sleep disruption further contributes to all major psychiatric conditions, including depression, anxiety, and suicidality.

...but I told myself, well, he's the expert, not me. Then I found resources, including Walker's Wikipedia page, that claimed there were inaccuracies and vital omissions in the book, and readers of my newsletter commented with links that some said added up to a full-on debunking. And now... well, I have a lot I could say or ask about this, but for now I'd welcome your thoughts.

I'll tread carefully here as I'm not someone who specializes in sleep science.

Look, there really are a lot of claims packed into that paragraph. While some seem plausible to me — for example, that you need sleep to have your immune system working optimally — some seem to go against my knowledge of the literature.

Let's take cancer as an example. Scientists check a claim like this by reading as many good-quality studies as they can, weighing up how robust those studies really were, and then coming to an opinion on the truth of the matter. Often the answer is “it depends” — for example, often people have a reason to not sleep much (such as anxiety or noise in a city) which themselves might be detrimental to health. Or perhaps lack of sleep is linked to issues but only in certain situations. Usually, we don't have the time to chew through all available studies on a topic unless it's our full-time job.

Another way is to read a meta analysis. In a meta analysis someone combines lots of studies using statistics. Meta analyses tend to give fairly straightforward answers but can lack that nuance we mentioned before. In this case, there is more than one meta analysis and they pretty clearly state that for most of us, no, the evidence doesn't suggest that getting less sleep causes cancer. Thankfully.

So, back to those claims. Do you need sleep to function well and generally feel OK though? Yeah, of course you do. You don't need neuroscience to know that, though, because you feel crap when you don't get enough. Could that lead to bigger problems down the line? The science (that I'm aware of ) says yes, but not cancer.

Something that strikes me about what you've quoted is how emotive it is. Personally if I read any health book whose opening paragraph ends in "X contributes to suicidality" I get the impression I'm trying to be scared in to some kind of marketing hook. It's very easy to get an emotional response without lying by using technical words like "contributes" so let's be clear here: People don't harm themselves primarily due to bad bedtime habits. They just don't.

Right. That makes sense to me, and seems to square with some of the more, uh, vehement criticism out there. Might a better word be "correlates?" Like, obviously this is conjecture, but I can easily imagine a situation where — in addition to the numerous other factors that might converge in suicidality — a sustained lack of sleep might contribute to, say, a breakdown. And that's where the disappointment is for me: it seems obvious that lack of sleep is correlated with lots of bad things but isn't necessarily a causative factor. Why isn't that enough? Why does it have to be sexed up to the point that it's open for criticism and the validity of the original message is lost?

I guess what you're getting at is that there's causality at different stages, and to different levels, and when you simplify too much you misrepresent the reality. If someone is in an emotionally dark place, cutting back on sleep even further is going to make things worse. No doubt. Will lacking sleep drive you to suicide? C'mon. Do I need to answer that?

Talking about correlations in this space can get quite interesting, but it's hard to condense. In essence, when analyzing complex medical conditions, taking averages of people who probably shouldn't be treated as equivalent can produce profound correlations that are either unhelpful or completely false. That happens especially when people get put into categories, which is how a lot of psychiatry works. (Simpson’s paradox is a favorite example of this problem in action). On the flip side, we can also know from experience that something is true — like, “getting enough sleep is helpful for practically everyone” — but the limits of mathematics mean we can't demonstrate it well.

Another thing to keep in mind is that complex statistics and statistical terms take a lot of expertise to understand. We regularly have "significant" correlations that mean next-to-nothing, "strong correlations" that we are uncertain about, and large increases in relative risk that are realistically negligible. We can even have strong significant correlations showing large relative increases in risk, only for those to be completely irrelevant to daily life.

Right. So, essentially, the answer is “it’s complicated!” But it does go to show how easily claims can be inflated, either by book authors, or in the minds of the general public. I’ve seen a lot of what seem like sexed-up or misunderstood claims in many pop-science books, no matter the authority of the author. What's your take on why this seems to happen?

I disagree that irresponsible statements tend to appear in books from scientists who are authoritative in the eyes of their peers. It certainly occurs with some who have made tenure, and especially those at some private, high-profile, US-based universities, but that's not the same thing. When I think back on extreme books like The Bell Curve the cynic in me can't help but think “all publicity is good publicity” — both for the Uni and the author. Writing a book doesn't grant any academic authority. It grants a paycheck.

Perhaps another factor is just the desire to finally speak your mind. Scientists spend their whole careers semi-muzzled by peer review.

I agree that exaggeration is not necessary. Science is riddled with incredibly interesting things and there are plenty of scientist communicators out there who are acclaimed for conveying nature's wonders in a responsible and engaging way. Attenborough, Hawking, Sagan... If you want something smaller, Pint of Science is an annual sell-out event in 26 countries and I've not yet heard anyone tell any porkies.

When it comes to Walker and Why We Sleep he’s addressed some of the criticism he’s faced on his website. What are your thoughts on this?

There's a lot of critique he's discussed there. In some parts, he walks us through some of the nuance I mentioned earlier, which should be applauded, as doing so is tricky. In other parts… well. It's not hard to find places where disagreement between studies has not been acknowledged. Studies disagree almost as a rule, and peer review makes us pare back our interpretation of results to something people can be reasonably sure of. Any work you come across relying on a single citation is immediately something you should take with a pinch of salt.

If this landscape is difficult for people with science qualifications to navigate, what hope do laypeople have?

It’s not that that science is necessarily difficult for a scientist to navigate. It is just very fiddly, which means it takes time. It's also that a scientist's view of truth is quite different. I'll try not to go down a philosophical rabbit-hole here, but I wish we had space for that because it really explains so much. In short, science thinks truth exists, but thinks that every way we can access it is fraught with error, so “how much doubt” we have is something we always need to factor in.

Think about accessing the truth more like a criminal court case. Get as much evidence as you can and ask if you have reasonable doubt left over. Then, maybe, consider not making a black and white life decision on it and, if possible, experiment yourself. Grab the cheap version of the product, somewhat increase consumption of product X, spend more time alone but don't leave your partner just yet, and so on.

Fair enough! It sounds like what I’m trying to do here. So, what sort of pinch of salt are you talking about here? How can we get a good idea of what's true or not?

How do you sift through evidence? Well:

At this point, Lee dropped a science bomb. The good kind, not the Manhattan Project kind.

I was expecting a couple of paragraphs on sifting through evidence the scientific way. He gave me nearly four pages, and they’re fantastic — I’m going to find them incredibly helpful, and I think you will too. In fact, they’re so comprehensive that I think they’re worth their own post, rather than being buried down the bottom of this one. Look out for it in your inboxes later this week.

As far as my personal self-improvement journey goes, I’ve decided that (Why We Sleep controversy notwithstanding) this week is Sleep Week. I’m going to give myself the best possible shot at getting a solid 8 hours shut-eye every night for seven days and see what happens. There is no guarantee of success — I meant to do this last week, but several nights plus a hospital trip with a sick toddler scuttled the idea entirely. However, something that is within my control is a brief retirement from my long, undistinguished Halo-playing career. I’ll report back next week.

As always, this newsletter is free. If you want to thank Lee for the extraordinary amount of time and effort he put into our correspondence (and you/your friends are musically inclined) go check out his music composition software, Musink. And the best way to pay me for this work is to share it around, so please think about who might find it useful, and send it their way.

Looking forward to your feedback in the comments!

— Josh

The issue is that Walker is British and that the hosts are North American. Brits often seem to talk a lot slower than Americans — particularly when they’re giving public talks! ↩

Sorry to everyone who recommended it! It’s just not for me. And no judgement at all on anyone who enjoys it. Everyone is different, and at the risk of pointing out the obvious, it’s OK to like things that others don’t, and vice versa. ↩