Hey Arnold: a review of Be Useful by Arnold Schwarzenegger

It's one of the better self-help books. But will it actually help?

There can't be many people in the world more genuinely impressive than Arnold Schwarzenegger. His life trajectory is the stuff of (living) legend: born into obscurity and relative poverty in Austria, he became the world's greatest bodybuilder, winning Mr Universe once and Mr Olympia seven times. Then he became a movie star, and then he became Governor of California. Now, in his old age, and with a lengthy Wikipedia entry's worth of success and controversy behind him, he's completed the arc by becoming a self-help guy. His new book – with a title riff on both the venerable, awful Seven Habits of Highly Effective People and the new, awful 12 Rules for Life – is Be Useful: Seven Tools for Life.

And it's pretty good!

Apparently, this article will take between 9 and 12 minutes to read. So here is a song of that approximate length to either enhance or detract from your reading experience.

It is very easy to dunk on self-improvement books, and I will be dunking on this one, a bit. But the fact is it's one of the better ones I've read, and I think there's much more good in the book than bad. This is partly because consuming conditions were as close to ideal as it gets: I did most of my "reading" via audiobook, which I listened to while lifting weights at the gym. But it's also just... pretty good. For one thing, it's short. Like practically all self-help books, it could be shorter, but (especially on audiobook) you forgive Be Useful this flaw because it's Arnie. He's winning, charming, charismatic, and often very funny. Most self-help books indulge anecdote about anonymous Janes and Johns to the point of inducing serious pain, but here all the apocryphal stories are about Arnold Schwarzenegger, and they're mostly true! He's famous to the point that probably half the world's population has built a parasocial relationship with him, and as such a lot of his book comes across as banter with an old friend. It also neatly avoids a lot of the most annoying stuff about plenty of self-improvement books. There's no one weird trick, no fast path to success. That's not to say the path Schwarzenegger lays out is any guarantee of success, but more about that later. For now, I think a pretty good précis of the book comes from the chapter headings:

- Have a clear vision.

- Never think small.

- Work your ass off.

- Sell, sell, sell.

- Shift gears.

- Shut your mouth, open your mind.

- Break your mirrors.

Now, let's get the dunks out of the way. It's self-help, so there will be no shortage of received wisdom, canards, and false facts, right? Sadly, this is indeed the case. Here's a point being made about how most things worth doing are worth doing mainly because they're hard:

Take something that most of us can relate to: becoming wealthy. It’s pretty remarkable when you realize that some of the least happy people you’ll ever meet are lottery winners and people with old family money. By some estimates, 70 percent of lottery winners go broke within five years.

This simply isn't true. As exhaustively detailed in Forbes, the "70 percent" statistic comes from a National Endowment on Financial Education symposium, where a single mention of one statistic got spread about by media. NEFE has since tried to debunk the fake statistic, to no success. "[It] is not backed by research from NEFE, nor can it be confirmed . . . frequent reporting — without validation from the NEFE — has allowed this ‘stat’ to survive online in perpetuity," they say. The other main source of lottery winner unhappiness is a 1978 study that compared the happiness of lottery winners, a control group, and people who had been recently paralysed in accidents. Not the greatest source of comparative happiness, right? The study also had a very small sample size – less than 100 people were studied – which, as we've learned, is a red flag. More recent, reputable studies have looked specifically at the happiness levels of lottery winners, like this one from Germany, and found that lottery winners tend to be – and stay – absolutely stoked. This is congruent with other modern research about money; that having enough of it is extremely helpful to your well-being. It's enough to consider the myth of the unhappy lottery winner completely debunked. (I do not know about the happiness statistics for generational wealth, and as I only have so much time, I will for now continue to be ignorant on this and many other matters.)

Why do I bring this up, especially at such length? After all, the passage is used to illustrate a point that's almost axiomatic; many accomplishments feel better if you work hard for them. I suppose it's a sticking point for me because – apart from the basic annoyance of seeing false information repeated endlessly – when a book gets something this basic wrong, it starts you wondering what else is mucked up.

I don't have to wait long before finding out. About a page later is this:

Imagine if Sir Edmund Hillary had been dropped at the summit of Mount Everest by helicopter, instead of trekking to it over two months in the spring of 1953. Do you think the view from the top would have been as beautiful? Do you think he would have given a shit about that other, smaller mountain he saw in the distance when he was up there? Of course not!

This one is even more of a nit-pick; of course the point of climbing Everest was the climb itself. I agree wholly with the sentiment. It's the details that are wrong. First, the helicopter. I know full well it's a metaphor but the fact is no-one managed to land a helicopter on the summit of Everest until 2005, 52 years after Hillary and Tenzing first climbed it. It was done by by French test pilot Didier Delsalle, and no one has ever managed to repeat the feat, because flying helicopters at the altitude of Everest is nuts. It's mostly done for world record attempts, making – ironically – flying to the summit in a helicopter far more impressive than merely climbing there.

The next problem is "Do you think he would have given a shit about that other, smaller mountain he saw in the distance when he was up there?" And here again I'm cursed by my knowledge of trivia I picked up from a childhood reading atlases and encyclopaedias: one of the very first things Hillary did on summiting Qomolangma was eye up other mountains, courtesy of the excellent view from Everest, and evaluate possible routes to their summits. Here's the relevant passage from Hillary's diary:

I noticed that the Barun approaches to Makalu looked very difficult if not impossible – a 1,000ft rock cliff. Tenzing and I shook hands and he so far forgot himself as to embrace me. It was quite a moment!

But even if I hadn't known that fact from my weird childhood, I'd have learned it from reading a book called Be Useful, by Arnold Schwarzenegger. In Chapter 2, we discover:

While [Hillary] was up there he saw another mountain in the Himalayan range that he hadn't climbed yet, and he was already thinking about the route he would take to summit that peak next.

Those goofs all occur within a few pages of each other. I'm not going to go through the whole book hunting for them, it'd take me a year, but I'm sure they're there. If they're anything like the ones I found, they don't matter that much. It's not like he's telling readers to drink bleach; it's just me being pedantic and easily annoyed by shoddy copy. This which is probably why I am a small-time newsletter writer and Arnold Schwarzenegger is Arnold Schwarzenegger. There are other issues, like things that I'm sure aren't meant to be taken seriously, but probably will be. Here's more Chapter 1, where Arnold – sensibly – recommends boxing up some time to work on things you actually care about instead of aimlessly scrolling on your phone or Netflix:

I can already hear the question coming from a bunch of you: What about time for rest and relaxation? First of all, rest is for babies and relaxation is for retired people. Which one are you?

Again, I get the point being made, in the form of a slogan that's practically a joke. But if a reader doesn't take it as a joke, they're going to have a bad time. Arnold, who has probably spent more time working out than I have hours in my life, knows this better than I ever will, but it bears repeating: adequate rest is required for many aspects of life, particularly when it comes to the gym. This is why untrained people who suddenly start "working out everyday" without seriously considering what they mean by that almost invariably burn out, often within a week or two. Competitive bodybuilders certainly do go to the gym more often and for much longer than normal mortals, but there are a couple of important caveats; they've (literally) built up to it, and they're training "splits," where one takes care to work one muscle group while carefully avoiding others that have just been trained to near-exhaustion. And it's especially annoying to read something like this in Arnold's book because, just a page prior, he says:

How many hours per day do you sleep? Let's say it's eight hours, because that's what all the current science says is ideal for peak performance and longevity.

And while this isn't really right either, it's correct enough for the average person, and it's certainly true for me.

The rest of Chapter 1 is about creating a bold and ambitious vision for your life.

"Vision is the most important thing. Vision is purpose and meaning. To have a clear vision is to have a picture of what you want your life to look like and plan for how to get there. The people who feel most lost have neither of those."

Look. There's a lot to unpack here. Suffice it to say that it falls into the classic self-help trap of assuming people have – or can take – much more control over their lives than is actually possible. "No one made them take that dead-end job," it says on Page 4. Except sometimes someone did make them take the dead-end job! Sometimes it's literal, and other times circumstances can be compelling to the point of compulsion. Self-help so often misses privilege; that circumstances are often dictated by quirks and flukes – of generation, of location, of gender, of so many other things, and all these are compounded by sheer luck, good or bad. You can have the most potential and greatest vision of anyone in the world and get killed by lightning, and that's it for you. Likewise, the world's hardest worker can get felled by, I dunno, long Covid. We can talk about positivity or the ability to choose your response to a given situation forever, but end of the day our choices often limited to the point of being illusory. You might call that cynical. I call it realistic.

Page 4 continues: "No one made them stay up late every night playing videogames instead of getting eight hours of sleep."

Well, fuck. Okay. You got me there, Arnold. Clearly, there's lots of life where you have no agency at all, but there are definitely some bits where you do. "Turn your TV off," Arnold says. "Throw your machines out the window. Save your excuses for someone who cares. Get to work." He's right. Privilege cuts both ways; self-help often fails to recognise it as a concept, but it is correct to point out that those with privilege often fail to use it effectively, or at all.

Chapter 2, Never Think Small, seems the logical extension of Have A Clear Vision. It's inspiring stuff! He suggests taking your current vision and making it ridiculously big. I do this in the pages of my gym notebook, because I am giving this self-improvement thing a serious shake. If you're reading this: I'm doing it for you.

Because there's a lot I'd like to achieve – I don't have any trouble dreaming big – I break it into sections.

- Writing vision: finish a book. -> Ridiculous vision: book becomes New York Times bestseller

- Gym vision: Do a muscle-up -> Ridiculous vision: bench press 150 kilogrammes.

- Newsletter vision: Post once a week, get 10k subscribers -> Ridiculous vision: get 1 million subscribers

The cringe just about makes my guts turn inside out. As I write, I wonder what gym-goers will make of a pile of wobbling viscera sitting on the lateral pull-down machine. Partly it's because it's embarrassing to publicly write down a vision, ridiculous or not. (Oh no, Josh! What if someone reads this?) It's also because it's statistically very unlikely to occur. Not everyone can be a New York Times bestselling author for the same reason that not everyone can win the lottery: what's more, if everyone who wanted to be one (or just wrote down "New York Times Bestselling Author" on a vision list) achieved their goal, the bestseller list would be meaningless.

Reading Be Useful, feeling equally inspired, skeptical, and self-conscious, I'm reminded of an RNZ interview with author David Robson, entitled "Great people don't always give the best advice." In it, Robson talks about Masterclass, and the founding idea that "you have these stellar people – award-winning authors, actors, billionaire entrepreneurs giving their masterclass on how to achieve what they did. And it just sounds so sensible, doesn't it? If you want to learn, you want to learn from the best."

But, he says, the model is fundamentally flawed. And it's not because the people who give the classes are grifters – they usually aren't. There's something else going on.

"I'm not saying it's a problem with any individual who is giving these classes," Robson says. "It's more that the psychology of giving advice is much more complicated than we might assume, and one reason for that is the phenomenon known as survivorship bias."

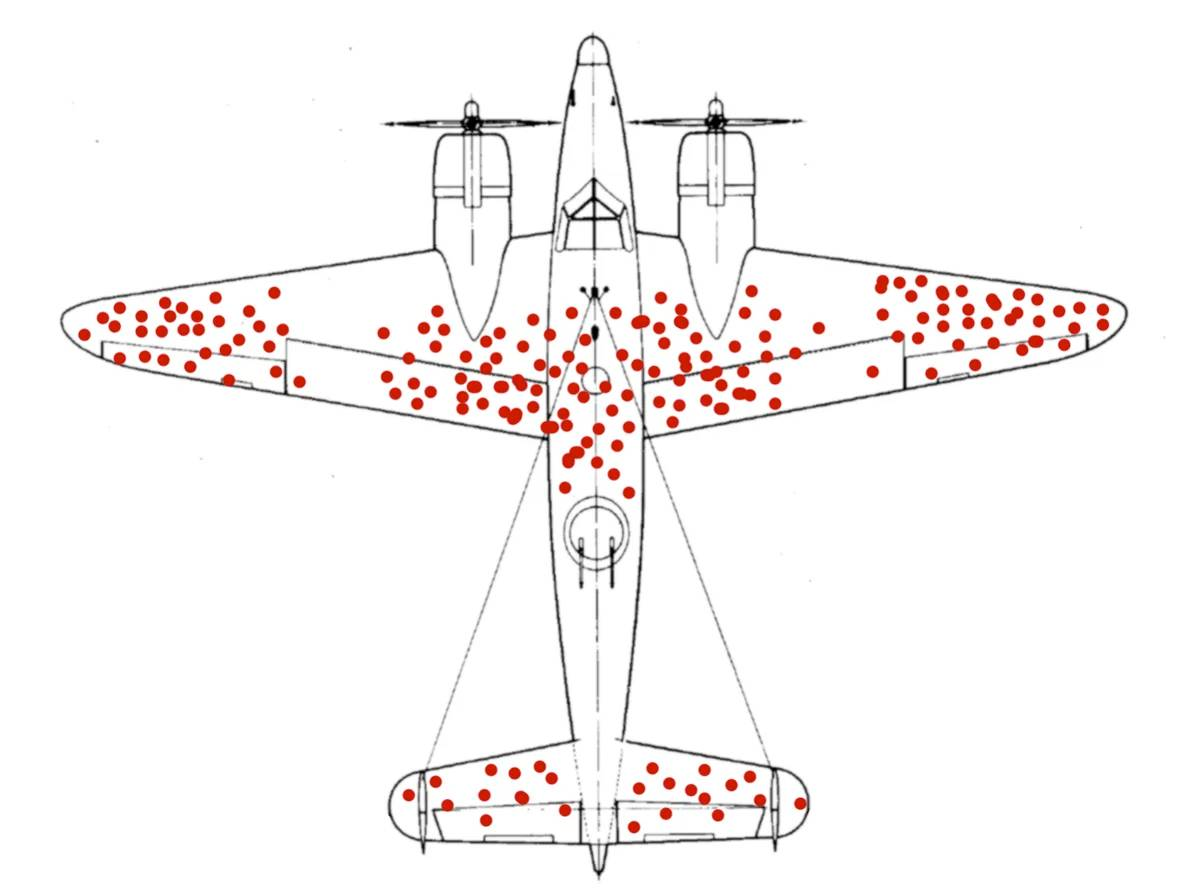

Robson cites a well-known example: bomber aircraft that returned from combat in World War Two tended to have suffered damage mainly in the wings and tail. Air Force brass proposed armouring those areas, but mathematician Abraham Wald suggested taking the opposite approach: recognizing that the aircraft that didn't return had been hit in vital areas like the engines, nose, and fuel tanks, he proposed adding armour to those areas instead.

The people who are most successful, Robson is suggesting, are often doing the lifestyle equivalent of suggesting that you armour up your wings and tail. It's not so much about the things that have happened to them, or that they've done; it's things that haven't happened.

"There could be many, many other people – thousands of other people – for each one of those [successes] who applied exactly the same routines and strategies, who had exactly the same ambitions, but just didn't achieve success," Robson says. "But we can't see those failures because they're invisible. We need to look at the people who didn't succeed as well as people who did succeed."

That, I think, is the best way of identifying a huge problem with self help as a genre, and Be Useful can't escape its gravity. Arnold's remarkable life is both his greatest asset and biggest liability as a self-help author. To his credit, he's a lot more self-aware than some other self-help authors: he opens a chapter with the admission that he'd have got nowhere without a lot of help from others. "I have a rule. You can call me Schnitzel, you can call me Termie, you can call me Arnie, you can call me Schwarzie, but don’t ever call me a self-made man," he charges. But even that doesn't change the fact that he's an extraordinarily hard worker who has had a lot of help and has also been very, very, very lucky. When you look back over your life and see huge success after huge success, it's easy to imagine that others can emulate it – and it's easy for readers to believe it too. As Robson explains, that not the case; it's mathematically improbable to the point of being nearly impossible.

But.

Let's look back at those ridiculous visions that made me – and possibly you – cringe so hard.

It might be statistically unlikely to become a New York Times bestselling author, but it's important to remember that all bestselling authors are subsets of another set: authors. People who manage an impressive bench-press are, almost invariably, people who bench-press. And newsletters with a million subscribers are a (very small) subset of people with 10 subscribers. (Or, in the case of the one you're reading, 2000. But who's counting.)

It's not so different from saying "a journey of a thousand miles begins with but a single step" or, more blithely "Shoot for the moon and you'll land among the stars." (Because I'm me, I felt compelled to look up the source of this quote, and imagine my surprise to find it's probably from Norman Vincent Peale, a Protestant preacher and author of the original toxic positivity bible The Power of Positive Thinking. Some amateur physics research also suggests that a failed moonshot might place you in a slowly decaying orbit around the sun, which means that your frozen corpse will land among a star, eventually. Stuff like this is why it takes me two weeks to write a book review.) Dubious quotations aside, it's true that if you want to achieve something big, achieving something smaller is a necessary pre-requisite. Even if great success is not important to you, then you can just get stuck straight into the small stuff. "Do you have any idea how powerful an hour a day is? If you want to write a novel, sit down and write for an hour every day, and aim for just one page. At the end of the year, you will have a 365-page manuscript. That’s a book!" Arnold says accurately, making me feel very seen for the many times I've tried and failed to write a novelsworth of book at a rate of one page a day.

Robson's skeptical thesis seems to be in agreement. "There's no easy way to just kind of absorb what another person's done, you actually have to kind of forge your own path through that expertise," he says.

With all caveats out of the way, I have to recommend Be Useful. It certainly seems no worse than any other self-help books, and all those books suffer from the additional drawback of not having been written and (in the audiobook version) read by Arnold Schwarzenegger. The book is frequently very funny, much more so than you'd expect, which makes it all the more amusing. Go back and read all the quotes I've supplied in Arnold's voice and get a mental preview. "In my experience, the fitness world, Hollywood, and politics are full of amazing people. They're also full of douchebags, pricks, and assholes. Navigating the gross parts of these worlds was like trying to move inside a set of Russian nesting dolls full of shit and hair gel." Now that's what I call a simile, and there's more where it came from. Arnold begins the audiobook by explaining that he's recording it in his home studio and apologising for any noises made by his pet donkey and pig. I had a hard time not cracking up in the gym.

Jokes – and all the the problems of self-help as a genre – aside, the book also wins major points for me for being less about helping yourself and more about helping others. This is the ultimate point of this enjoyable, short book, and it's a very good one: No matter who's telling you to do it, Be Useful is good advice.