The #1 thing most adults wish they could get better at

Gidday Cynics,

This newsletter has been a long time coming. This is strange, because it’s one of the very few areas in self-improvement where I already understand the topic, I’m reasonably proficient at it, and I even know a bit about how to teach it. What’s more, it’s a popular subject. A couple of weeks ago, when I asked if people would like to know more about how to draw, people were keen. A bunch of you shared your stories in the comments:

I’d love to hear what you have to say about art in education ~ at school, all I ever wanted to do was succeed in art.

I was good at it, and didn’t give a fuck about any of my other subjects. When my results came back from my 7th form painting portfolio submission, I had failed, due to “too much pen and not enough paint”. It absolutely crushed me and I didn’t draw a thing for at least 4-5 years after that…

I WISH I could just make art. But my brain keeps getting in the way.

The above is, unfortunately, a common experience. Many kids have an instinctual love of art burned out of them by the school system, and this later haunts their adult efforts at visual creativity. Hopefully what I’ve got to say will show a way around it.

Love love loved this! Inspiring and relatable, esp as someone who has just started sketching, largely because words - for so long my main creative outlet - have begun to fail me.

Oof. I know that feeling. But it’s fantastic to have another outlet that isn’t writing, and in my experience, one can usefully inform the other.

I’d love to read more about your process and philosophy around art. I’m one of those who gave up as a kid because I was only good at reproduction but couldn’t draw anything realistic from memory, or creative that wasn’t based on a real thing.

Again, this is really common! In particular, being able to draw realistically from memory is bloody difficult — but it really is an acquirable skill.

I would love a bigger ‘art’ post. My daughter loves to draw but sometimes she will throw the pencil down & refuse to go any further because it’s not turning out the way she envisioned, and yet her wee drawings have so much joy and vitality in them and I don’t want her to lose that. It would be great to share some of your wisdom with her - she thinks your painting of Bianca is amazing too, so words from the actual artist will carry some weight (no pressure, haha!)

Once more: this is incredibly common. A huge number of kids go through a stage where they feel powerfully compelled to draw “realistically” but the shortfall between their ambitions and ability leaves them frustrated. Often, adults are of no help at all, because it’s easy for their attempts at support to backfire horribly. “Oh, honey, that looks wonderful!” is — in the mind of a child who’s trying to draw realistically — an obvious, patronising lie. It objectively does not look wonderful. And saying “Oh, don’t worry, it doesn’t have to look realistic! Just look at Picasso!” or something similarly well-meaning can be even worse, because you’re ignoring what they actually want to accomplish: to draw something that looks like what it looks like. And that leads us straight to the beginning of our lesson:

Nothing looks like what you think it looks like.

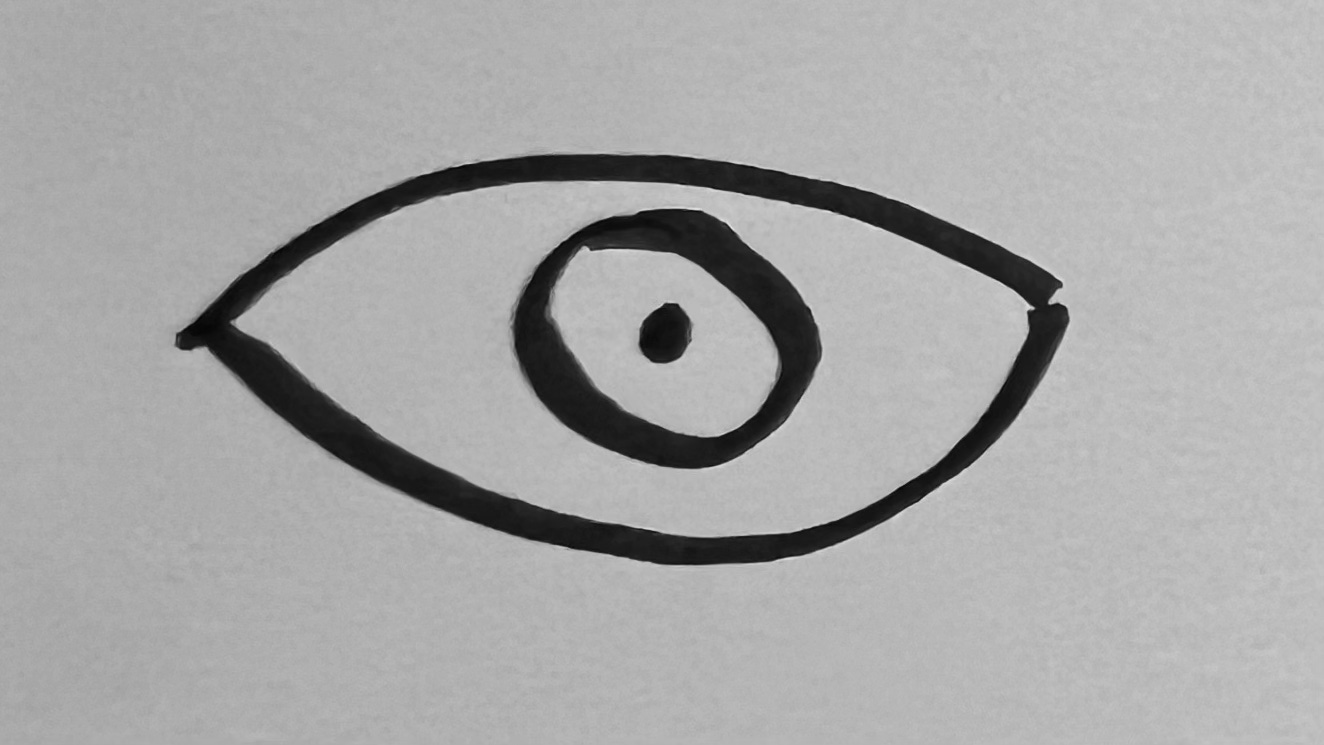

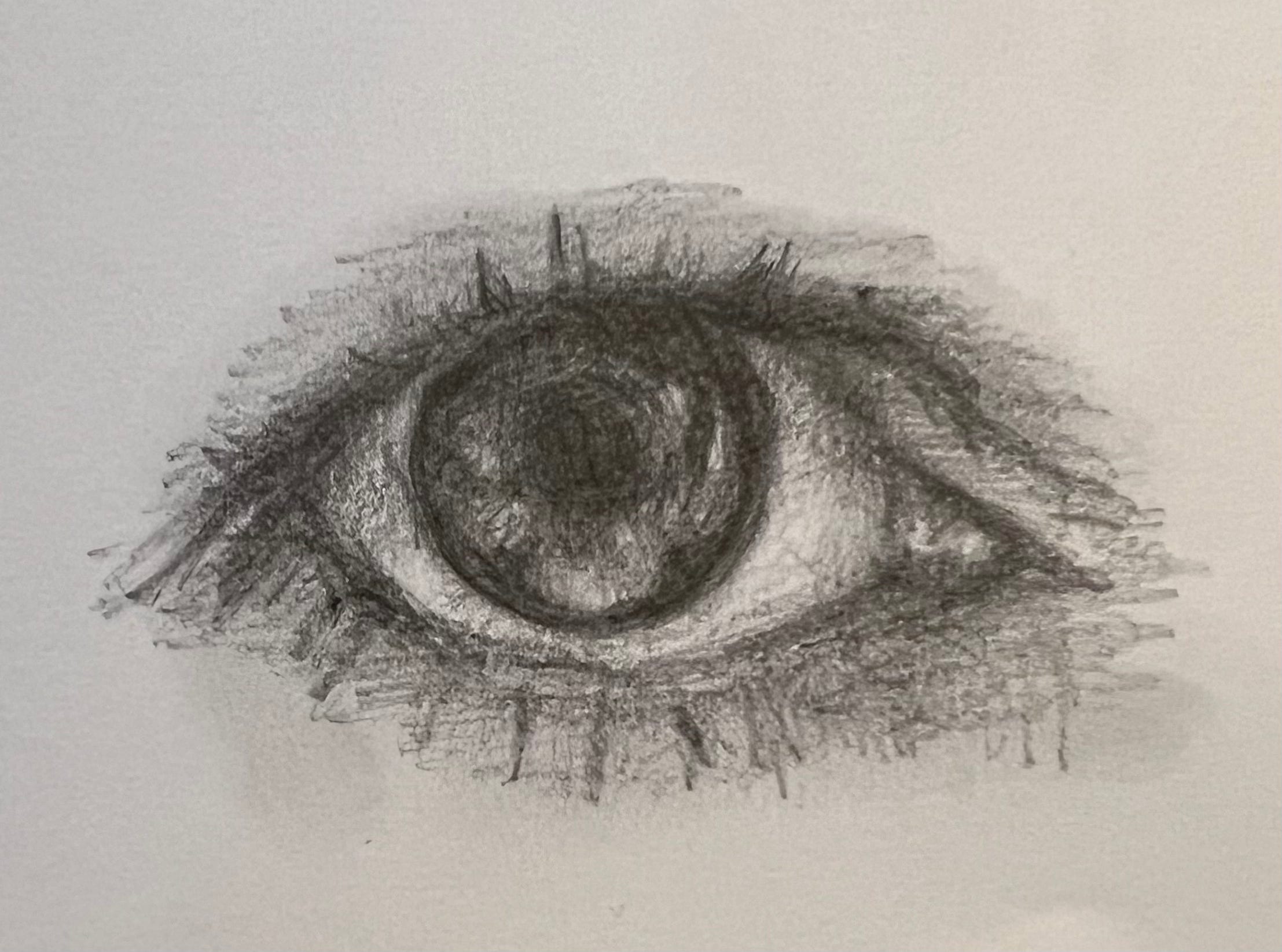

Look, I drew a thing. What do you see? It’s not a trick question: just react honestly, and then scroll down.

If you said a smiley face, well done! This is a fundamentally normal way to react to what I just drew. You might even have smiled back. As scientists at Australia’s Flinders University found, our reaction to a smiley face (or emoji, or emoticon) is a fascinating “integration of a learned and innate response.”

But with all that said, it’s just a circle, two dots, and a curved line. It’s not much like a face at all. To make the point, imagine what emoji would look like with realistic human features. In fact, to save you the trouble, I’ve found an example.

Distressing, eh?

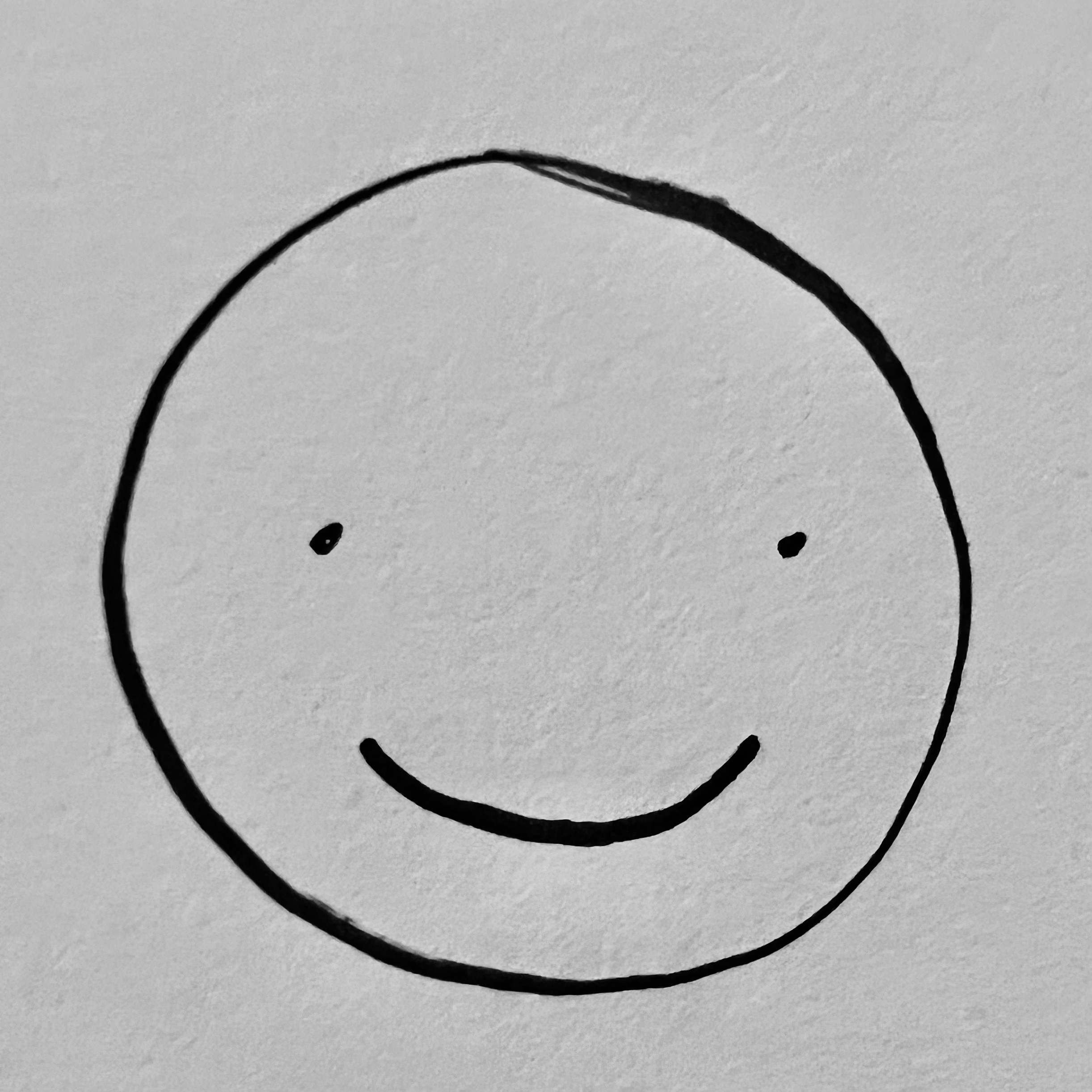

What about this one?

You can see where I’m going with this. A real eye is a ball of gristle and blood and goo, moist and gleaming, surrounded by folds of skin, hair, and greasy membranes. The window to the soul, perhaps, but only in the most Lovecraftian sense. Obviously, those curved lines and dots up there aren’t an eye, and the longer you look at it, the less like one it appears. It’s just a symbol. So why do we see it as an eye?

There are a number of answers to that question, and they go some way toward explaining why drawing is so hard for many people. But the easiest (if not strictly accurate way) to explain the answer is to flip the question on its head: it’s not just that we see a symbol as an eye; it’s that we see real eyes as symbols. And, as it turns out, pretty much everything else.

There’s nothing wrong with this. We need symbols, least of all for reading. Children almost invariably draw symbolically. Adults who haven’t learned to draw “realistically” can still draw symbols; this is the reason that self-confessed terrible artists can absolutely slay at Pictionary while people like myself can be quite bad at it. And I need to be careful: I am using metaphors to plaster over several lifetime’s worth of art instruction, psychology, and neuroscience. Obviously, we do not literally see the world as hieroglyphics1, but there’s some weird shit going on that only becomes clear when you either dig deep into medical literature or try to draw something realistically, and the seeing-the-world-as-symbols metaphor will start to make sense.

Let’s talk seeing. As you’d expect, seeing begins with the eyes, but they’re only part of the picture. The rest is (neuroscience term incoming) brain stuff. Seeing is important to humans, and enormous brain resources are dedicated to it. Weirdly, images are processed in the back of the brain, with the optic nerve running all the way from the back of the eyes to near the rear of the brain. What’s more, the nerve flips half-way, to ensure that the images from your left eye are processed by the right side of the brain (which runs the left side of your body) and vice versa.2 Oh, and because of how lenses work your eyes receive images upside-down, like looking through binoculars backwards: it’s your brain’s job to flip them up the right way. Confused? Don’t blame me, blame either a. evolution, or b. the Creator’s ineffable grand design. It amounts to the same thing in the end.

This is just the start of it, though. Only the central part of your retinas are able to perceive colour well: but the fact that you appear to see everything in rich colour is a trick performed by your brain. Ever seen a cat out of the corner of your eye but it’s actually a rubbish bag? Brain stuff: your grey matter simulates what things might be before it concludes what a given thing actually is. Are you able to tell how far away objects are, or catch a moving ball? Brain stuff. And can you tell instantly that your attempt to draw a self-portrait or a motorbike or a school-curriculum-mandated scene of a “Spanish” helmet sitting on a New Zealand beach does not look like what it’s meant to look like but — infuriatingly — you have no idea why, or how to fix it?

Yup. Brain stuff.

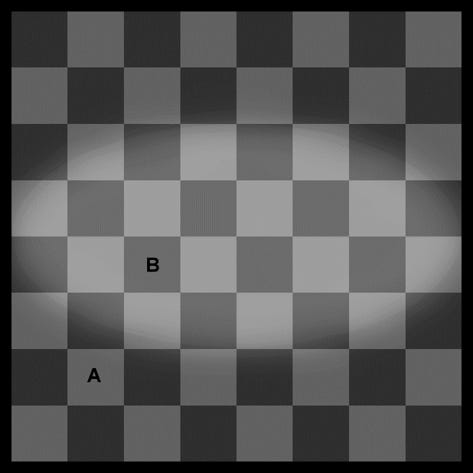

It can sometimes be alarming to realise what you see is not exactly what is, but it’s true, and can be proven with optical illusions. Here is one I nicked from the University of Queensland:

Most adults cannot draw

It bears repeating: if you cannot draw, you are not alone. In fact, you are part of a large majority. You see art all the time, and this may make you think that drawing is a common skill. It is not.

Science has had a good crack at trying to understand how the cognitive conditions I’ve outlined relate to drawing. A 1997 paper titled “Why Can’t Most People Draw What They See?” concluded that:

(a) motor coordination is a very minimal source of drawing inaccuracies, (b) the artist's decision-making process is a relatively minor source of drawing inaccuracies, and (c) the artist's misperception of his or her work is not a source of drawing inaccuracies. These results suggest that the artist's misperception of the object is the major source of drawing errors.

In other words, there must be some brain malarkey going on in how humans perceive objects that specifically relates to drawing. It’s not a matter of being clumsy, either. The study found that non-artists who struggled to draw recognisable objects or faces could still trace a photograph just fine. Yet “misperception of objects” is also clearly an oversimplification, which the authors admitted; perception of objects is something that most humans are fundamentally good at.

Since then, research has continued. “The difficulty adults find in drawing objects or scenes from real life is puzzling, assuming that there are few gross individual differences in the phenomenology of visual scenes and in fine motor control in the neurologically healthy population,” begins “The genesis of errors in drawing,” a 2016 review of the scientific evidence on the topic in Neuroscience and Biobehavioural Reviews. “However, the majority of adults are rarely able to put down a passable likeness of their visual experience onto paper.”

This is Science for “look, sure, brains are different, but by and large most people tend to process images in similar ways and most people can pick up a pencil. So why is nearly everyone so shit at drawing?”

Their paper reviews a huge swathe of the available literature to come to the conclusion: it’s complicated. Just ask our resident scientician, Dr Lee Reid:

“The biggest factor is that the visual system breaks down into different pathways that interact but progressively become less and less connected to each other — and at the end of one of those pathways is your hand,” the actual neuroscientist says. “That pathway has evolved to guide your hands — or your feet or your head or whatever — towards objects or away from objects, so you can catch a ball and things like that. That uses a very different set of skills to identifying what something is.”

These different pathways, Lee explains, lie at the heart of why people often find drawing so different: there’s a physical distance between them in the brain and they aren’t very connected to each other. Imagine two large motorways, both with different destinations, and the only way between them is a dirt track that’s prone to flooding. Brains are creatures of habit, and forming new neural connections is energy-intensive, especially in adults. So, when the brain does try to connect the two different tracks — as in, when a non-artist tries to draw something — it prefers to avoid the dirt track, sending you on a detour via the well-travelled roads of Symbol Country.

“The processing in the middle breaks everything down to symbols, which you already have in your head. So it's less that people don't perceive things, it's just that symbols are coming into play,” Lee says. He suspects that the ability to draw simply isn’t as evolutionarily useful as the ability to, say, pick things up, throw and catch objects, and know what stuff is. “Probably, when you're learning to draw, what you're actually learning to do is to connect the ends of those pathways a lot better.”

So, informed by these papers and my discussions with Lee, here’s my crack at what’s going on in the brains of adult non-artists when they try to draw something.

When you try to draw, you are faced with not just your brain’s penchant for symbols. You face that instinct plus dozens of optical illusions and cognitive delusions — perhaps more. You are trying to form new neural connections over an unfamiliar path that your brain would rather not use, which is always difficult, especially in adults. In all probability, you also face an inner critic who is perfectly capable of seeing that what you’re drawing doesn’t look anything like real life and isn’t shy about telling you in the strongest possible terms. And you are expected to (or are expecting yourself to) instinctively deal with or bypass this cognitive onslaught in order to render something realistic.

Without training, or a rare quirk of neuroatypicality, it’s like trying to do calculus without ever having learned how to add 2 + 2.

So, if you’ve ever beaten yourself up for not knowing how to draw, you can stop. It’s a miracle anyone learns to draw at all.

But, also miraculously, it’s almost certain that you can still do it.

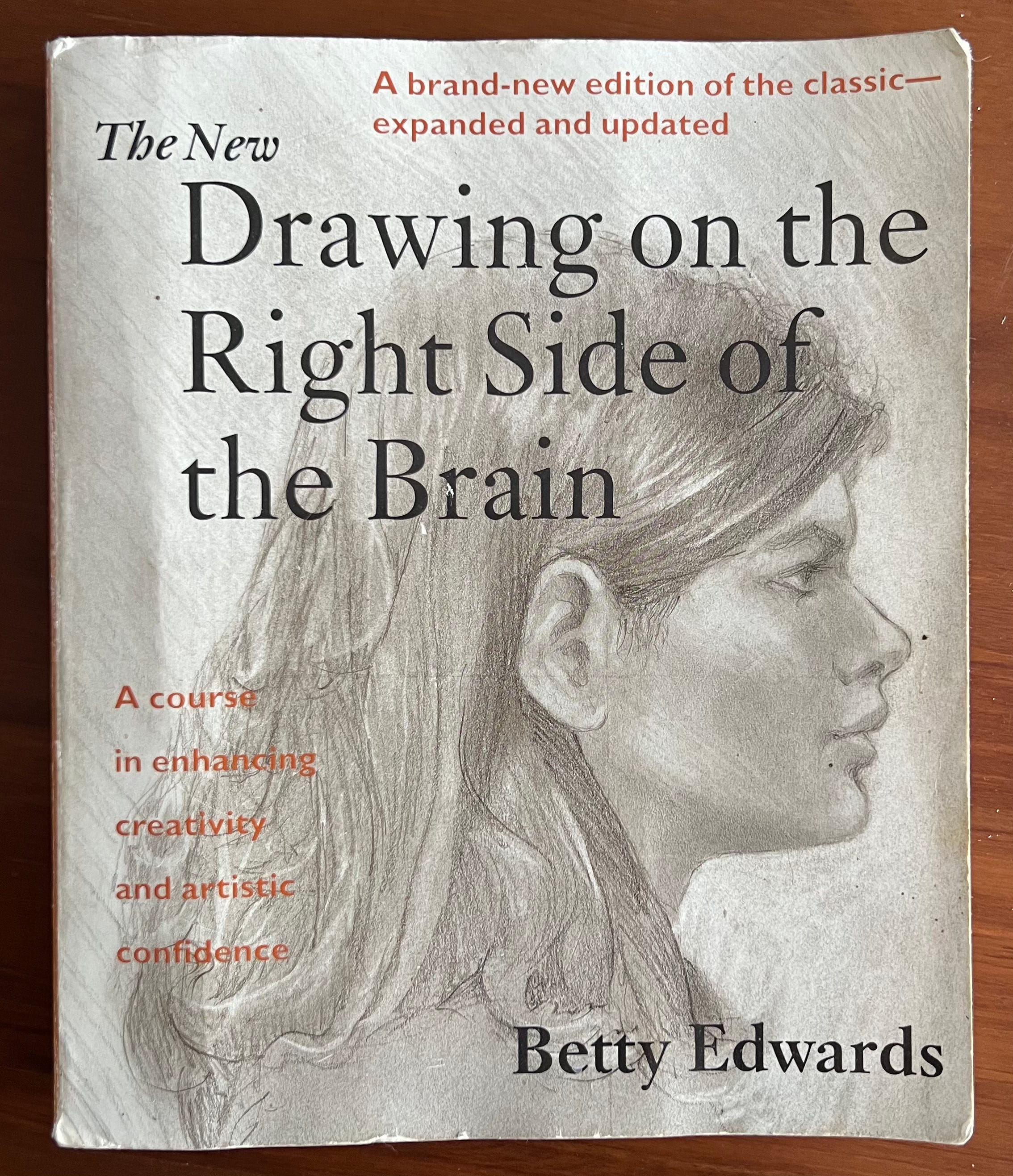

Of course, there’s a self-help book for that. Luckily, it’s a very good one.

Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain is an instructional book by Betty Edwards, former professor emeritus of art at California State University. First published in 1979, the book’s fundamental thesis is that abilities we’re taught to prioritise — writing, arithmetic, spoken language — are mediated by the left side of the brain, and more “holistic” abilities like drawing live on the right side of the brain. These are often repressed, but can be unlocked. It’s a fascinating theory, and it’s wrong. As partially detailed above (and explored much more thoroughly in the four decades of neuroscience and psychology research since 1979) it’s much more complicated than just left brain vs right brain.

However, where the book fails as science, it succeeds as metaphor and pedagogy. There is a good reason that, when asked how to learn to draw, working illustrators will often respond “start with Edwards.” When I first read it, as a kid who was “good at drawing” but was perpetually frustrated with the process, it blew the doors off my artistic development. Here’s the tenet that did it:

Drawing from life is just tracing what you can see.

This sounds ridiculous so please indulge me to prove the point. If you’re a non-artist, have a go at this exercise. You’ll look a little silly so either find a private spot or be prepared for intelligent questions from curious colleagues. Stop whatever it is you’re doing and look around you. Hold your head still. Shut one eye. Use your finger (or a pencil or pen) to trace the outline of objects around you in the air. It doesn’t matter what the objects are: a mug, chair, bunch of bananas, vase of flowers, a curious two-year-old. The more complex, the better.

Could you follow the outline of an object with your finger? If so, congratulations, you can draw. Drawing is just doing the same thing — on paper.

I understand this might seem too simple, especially for adults who might have struggled to draw many times and whose petulant inner 12-year-old art critic is even now stomping off in a huff.3 But that’s really it. This one simple trick™️ (artists hate it!)4 can help blaze a new neural path through years or decades of adverse conditioning. Again: take what you can see, and trace it, on paper. That’s drawing.

The other vital thing that Edwards offers is a way to disconnect from your inner critic. You’ll need the critic later in your drawing journey, but at the very start it’s a nuisance that simply can’t comprehend why your drawing doesn’t look like what you want it to. The right drawing exercises can help you first quieten the critic and then offer it gainful employment as an ally, with a minimum of self-scolding or hissing “shut up” to yourself.

But here’s the funny thing: perhaps because I already liked drawing and did a fair bit of it, this advice and a few basic exercises was enough to take my drawing to another level. I never actually finished reading — or working through — the book.

So. Want to go through it together? If you’ve been wanting to learn how to draw, this might be a great opportunity. Let me know in the comments, or reply to this email.

In the meantime, here is a time-honoured, counter-intuitive, meditative, and often quite trippy exercise that appears in DOTRSOTB, which contemporary neuroscience5 suggests actually has a lot to do with how artists draw all the time, and which we will use to temporarily unhook drawing from your ability to self-criticise. It’s called:

Blind contour drawing.

YOU WILL NEED

A pencil

A blank sheet of paper

10 to 20 minutes or so of free time

Hands6

Here’s how to do it. Sit at a table or desk. Put a piece of paper down. Take your drawing hand — it doesn’t matter if you’re right or left dominant — so you’re holding a pencil poised near the middle of the paper. (If you like, you can tape the paper to the table, to make the next steps a bit easier, but it’s not required.) Now, turn away from the paper, so you can’t see it, but leave your hand where it is, ready to draw. Position your non-drawing hand so you can see it clearly.

Now draw the lines of your hand — without taking your pencil off the page or looking back at the paper. Do it very, very slowly, as if you are tracing every fine line and detail in your hand with the pencil tip. This will drive your inner critic nuts. If you’ve ever doubted you have one, this will dispel this notion. Tell your critic it can look at the drawing — later. If you’ve done mindfulness meditation, this may feel familiar. Note feelings or thoughts and just keep drawing. Draw all the lines in your hand. Look for finer details, then draw them. It may feel a bit weird. It may feel very weird. You may feel as if your hand is a fractal infinity, an endless spiral of detail down to the very atoms, a masterwork of extraordinary and strange proportions that you’ve never truly witnessed before. Or you may be slightly bored and feel a need to go to the toilet. Roll with whatever comes up. If you accidentally take your pencil off the page, put it back down and keep going.

Then, after at least ten minutes, look at the drawing.

If you’ve done it according to the instructions, it will look like nothing at all. Or perhaps a topographic map, or a river valley, or strange, indecipherable writing. As always, your mileage will vary.

This exercise achieves two aims: it helps you learn a vital drawing skill — tracing the contours of reality — and produces something so abstract that your inner critic should have absolutely no idea what to do with it. Instruct it. Appreciate what you’ve made. “Look,” you can say to yourself. “I created something weird and beautiful, for myself, and for its own sake.”

And that’s art.

Thanks for reading. This article, like all my stuff, is free. If you have found it helpful, please share it, and encourage your friends to subscribe.

See you in part two, where we’ll discuss why you (almost certainly) never learned to draw as a kid, even if you did art at school.

If you do see in hieroglyphics, seek medical attention. ↩

I am oversimplifying. There's some overlap because you (probably) have two eyes, and what's in front of you is left of one eye and right of the other. ↩

I mention 12-year-old critics for a reason: 12 is around the age that artistic development often stalls out in children that don’t get adequate drawing instruction. If you’re a non-artist and you’re in a psychoanalytical mood, try drawing something complex and difficult, like your own or someone else’s face. You’ll probably have a bad time, but don’t worry about that for the moment. Instead, try to analyse the internal criticism that crops up. What does it “sound” like? Does it have a voice? What does it remind you of? Of course, your mileage may vary, but mine sounds a lot like a snot-nosed kid saying “Oh my goshhhhh this drawing suuuucks” and I don’t think that’s a coincidence. ↩

They don’t. Artists generally love it when more people learn art. ↩

Article too long, so this goes in the footnotes: new evidence suggests, incredibly, that skilled artists spend much of their time drawing blind. They’re looking at the subject of their drawing a lot more than they do at the drawing itself, which suggests the brain has learned to simulate what the drawing hand is up to. Here are Chamberlain and Wagesman with their explanation, my emphasis added: Large parts of the time spent drawing are spent ‘blind drawing’ during which time the artist does not look at his drawing hand. In a functional neuroimaging study, Miall et al. (2009) found that the act of drawing blind remains consistent with visually guided action, despite lack of direct visual input. ↩

You don’t actually need hands. You just need something complex to draw and a way to hold a pencil. I’m not being snide; history is replete with extraordinary examples of disabled people who do not have full or (any use) of their hands learning to draw. As a kid, I did some watercolours with our neighbour. Her mother had been poisoned by thalidomide while pregnant, and she was born with deformities in her limbs. Despite this, she was an excellent painter. I’m very grateful to this lovely person, who was very generous with her time to a curious 10 year old. ↩